The History of Edinburgh’s Greenspace (Pt. 1)

,

This is the first in a series of blog posts on Edinburgh’s greenspaces, by postgraduate student, Jamie McDermaid. Jamie is studying Environment, Culture, and Communication at the University of Glasgow – with a particular interest in urban nature. This blog post looks at the history of Edinburgh’s urban development from the late 1700s to early 1900s. It explores how green spaces were formed through the unique growth of the city in this period.

Moving Beyond the Walls

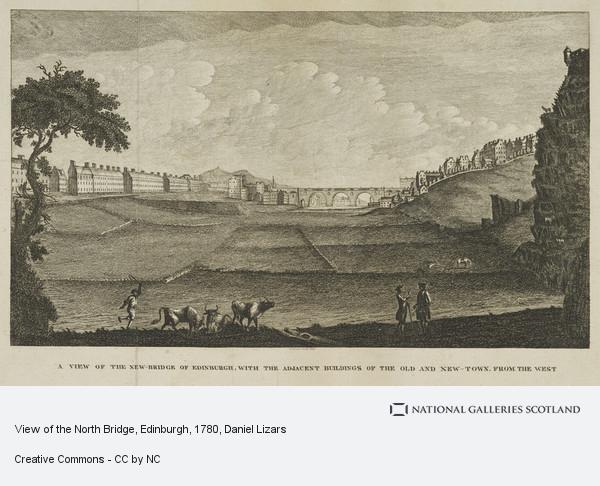

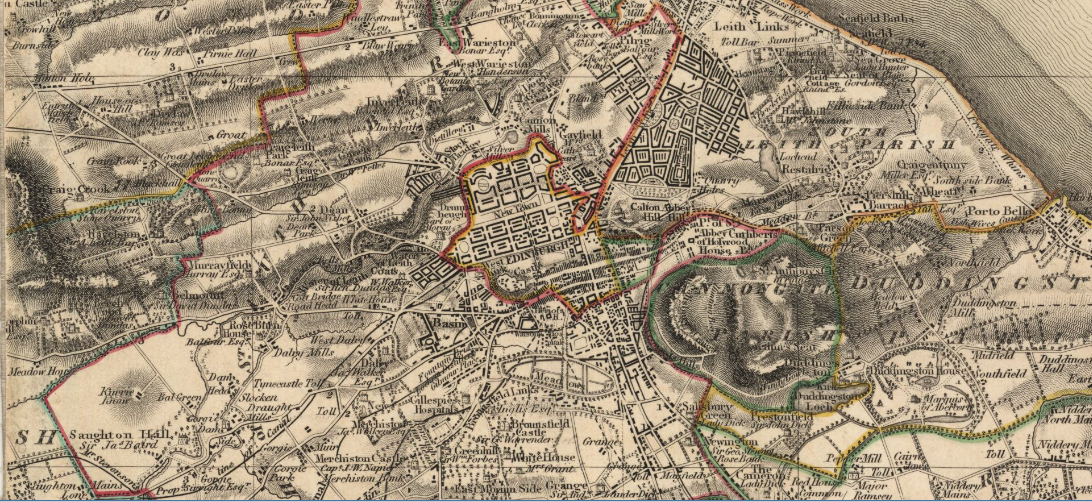

In the late 1700s, Edinburgh was a relatively small, self-contained settlement. This is because it was restricted by the city walls which had previously served as a vital defence during conflicts. However, with congestion increasing, and upward building reaching its limits, the development of the city had to go beyond the walls. So, in 1766, the New Town was planned and thereafter built. It was then continually expanded upon over the next 50 years.

A New Garden Town?

Before congestion became an issue, Edinburgh had actually been a fine example of a medieval garden city. It was full of green spaces, interspersed amongst its buildings. Of course, before the rigid boundary of the walls was discarded, these green spaces were gradually built over. This meant that its garden city character was ultimately lost. To remedy this, the plans for the New Town were designed for Edinburgh’s wealthier residents. For them, it was an escape from the increasingly poor living conditions in the Old Town. This New Town involved multiple green spaces, with an emphasis upon the picturesque concept of aesthetically pleasing, and complimentary, buildings and landscapes. Princes Street Gardens was even designed by an influential landscape painter! From a very early stage then, there was a clear emphasis on preserving and valuing the visual qualities of Edinburgh through greenspace.

Romantic Influences

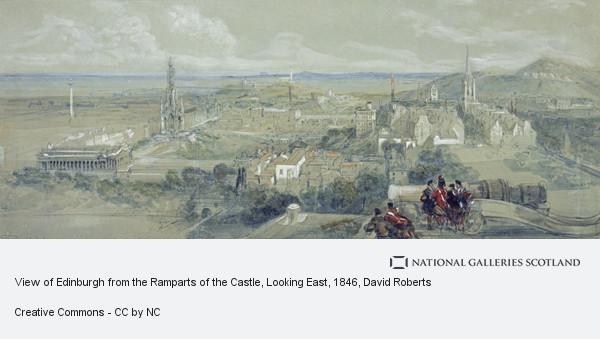

From the early 1800s, Edinburgh’s green urban development was influenced by Romantic thinking: the idea was to keep space for nature in the city as a response to mass industrialism. This Romantic influence on urban planning was not necessarily grounded in pastoral ideals though. Rather than keeping greenspaces for the urban idealisation of a rural lifestyle, there was a more practical goal of simply making the city a more pleasant and healthy environment to inhabit. In the early stages of this development, the city was still largely viewed as a unique, self-contained town surrounded by vast, open countryside. The French traveller, Louis Simond, admired this particular quality of Edinburgh in 1810. But by 1850, as the boundary was continually expanded, this quality was all but lost. Many of the greenspaces admired by Simond, however, were still maintained within this urban sprawl.

The City and Country as One

Robert Louis Stevenson grew up in this period, when the gradual spread of development was mixed in with the maintenance of wide, open greenspaces. He describes ‘many an escalade of garden walls; many a ramble among lilacs full of piping birds; many an exploration in obscure quarters that were neither town nor country’. He looks back fondly upon this time where the city and the country were one and the same, but in 1889, at the time of writing, he laments the gradual loss of these wider greenspaces as the relentless drive to continue developing swallows up more and more land. Whilst Edinburgh wasn’t quite so heavily influenced by the industrial revolution as other cities, the population was still rapidly increasing and actually quadrupled over the course of the 19th Century. Of course, this caused much greenspace to be lost.

This blog will be continued in a subsequent post.

Jamie McDermaid